Writing is not Linear: The Making of The Eyes, The Sword, and The Remedy

Paperback of The Eyes, The Sword, and The Remedy

Introduction

All their lives they believed they’d fulfill The High King’s Prophecy…

When the threat of demonkind returns, led by the Lord of Demons, Dyardaridge, the three half-brothers Crow, Sage, and Lance are unprepared despite the unique abilities they were born with.

Knowledge, strength and healing magic do little when faced with weakness, and after being separated by their mother and two guardians, Lance’s strength is shaken with unmade decisions, Sage takes pride in his magic but lacks faith in his future, and Crow’s ability to learn anything from a single glance cannot reveal the truth behind his mother’s past, and why she’s so desperate to escape it.

Alanna Russell's The Eyes, The Sword, and The Remedy takes you into a fantastical world wrought with mystery, magic, broken trust, and heartbreak.

When walking the line between obsession and illusion, how can you know who has your best interests at heart, or whether you merely prolong another’s fantasy?

That was the final rendition of the synopsis for The Eyes, The Sword, and the Remedy. It may seem simple, but there’s still room for improvement. One might assume that an author—being the one who knows their story best—would find writing the synopsis easy. In reality, that’s often far from the truth.

This synopsis condenses an 830-page novel into less than a page. It could only be finalized once the novel itself was complete—I needed to fully understand the story arc, flesh out the world, and develop the characters along with their relationships. What began as a simple concept during a drive through the mountains unexpectedly grew into a five-book series. The first novel was just the beginning, taking shape over the course of eight years. Like the synopsis, writing it was far from simple—but it was an incredibly rewarding journey.

Many imagine an author seated at a laptop, tea in hand, beside a sunlit window. They picture neat stacks of notes, a tidy desk, and a story that begins effortlessly with the prologue or first chapter. In this vision, the author writes for hours, moving from beginning to end without edits, struggles, or detours—turning an idea into a clean outline, a first draft, and then a published book in neat, linear steps.

To most, an author is a studious figure—intelligent, poetic, and unwavering—someone whose process flows in a straight line from inspiration to completion.

I’m Alanna Russell, and this is the story behind The Eyes, The Sword, and The Remedy. From the first spark of an idea to the final page, my journey as an author proves that writing is anything but linear.

Origins

“If you have many ideas, and don’t know where to start, just write it.

While an idea can take you so far, writing it is what you can control. Either as a screenplay, a novel, a script, or detailed bullet points—just write it. Figure out what to do with it once it’s written.”

Cris Cameron, Author of Cover of Darkness

Whether or not it’s common, I’m the kind of writer who begins with characters and then watches the world build itself around them. I firmly believe characters write their own stories, define their own worth, shape their own vision, and fight for the causes that matter to them. They’re like children—you can’t force them into what you want or expect them to be. You give them tools, and you let them carve their own paths.

But unlike a parent, I’m more like a scribe or a squire, recording the events and conflicts of a world that grows on its own—not its god. The characters are what began this journey and literally define the name: The Eyes, The Sword, and The Remedy.

Their world formed around their titles, which came from three names I fell in love with: Crow, Sage, and Lance. At first, the concept was simple—they were grand aides to “the king,” whoever he might be. The Eyes (a crow), the Healer (herbs like sage), and the Sword (a loyal weapon) would stand at the king’s side and guide him into battle. But at the time, I imagined them as objects or perhaps animal companions—not three boys.

That concept grew into something much bigger later on.

2017-2020

In 2017, I was driving through Banff National Park—specifically the stretch with no satellite signal. At the time, I was working on a graphic novel, and my team shared a collaborative music playlist

Somewhere along that winding road, Always Summer by Yellowcard began to play, and I slipped into a kind of trance. My hands steered on muscle memory while my mind drifted back to a concept I’d been toying with: the eyes, the sword, and the healer serving “the king.” But this time, they took shape—not as objects or symbols—but as three boys.

I pictured them on horseback, riding down a mountain. Surrounded by the same kind of sweeping scenery, I fleshed out their personalities and their abilities. For the next hour of driving, the same scene replayed in my mind: they’d ride down, the vision would reset, and they’d ride again.

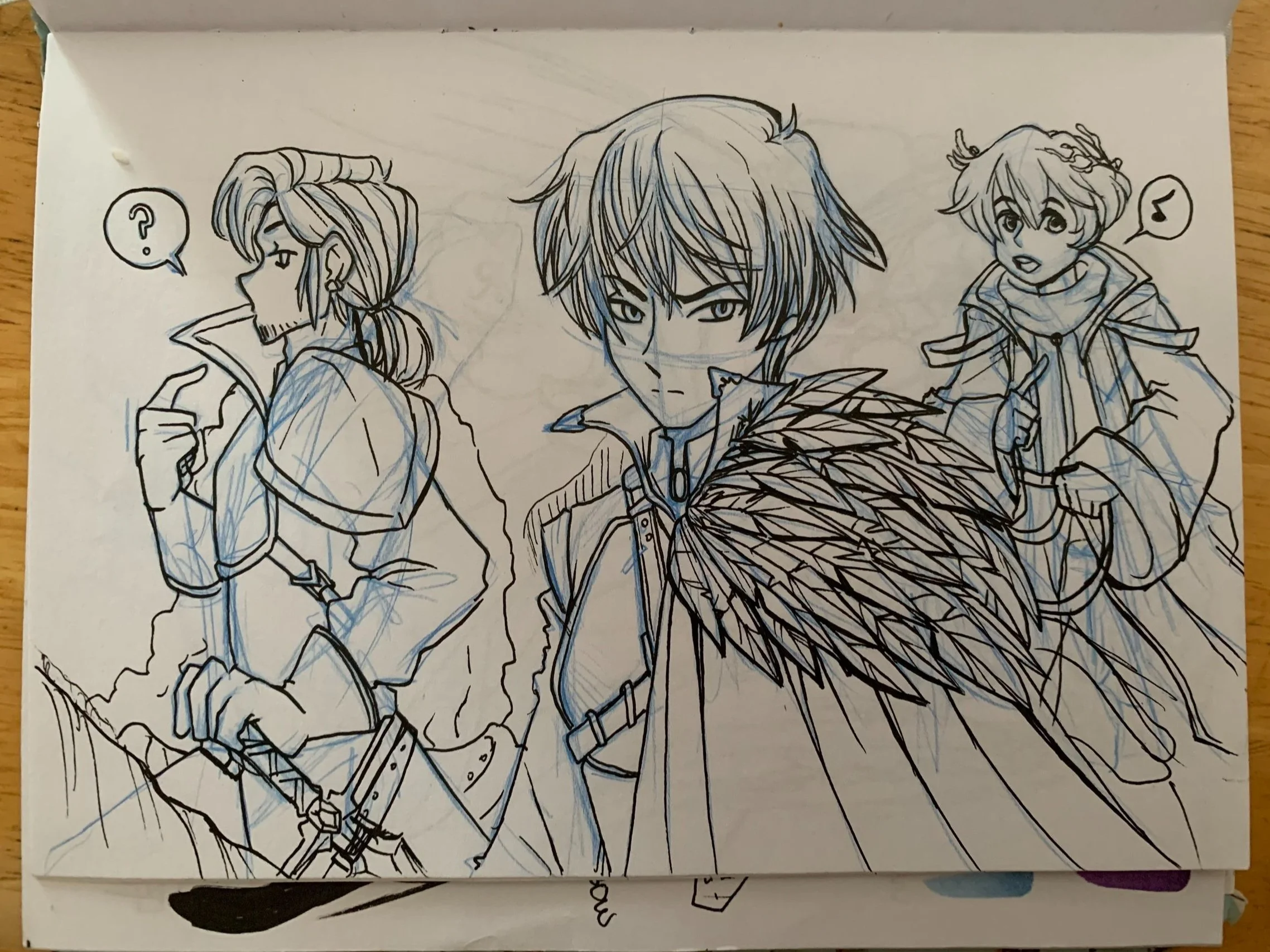

By the following weekend, I still couldn’t get them out of my head. So I drew them.

It wasn’t until they finally broke through the treeline that I saw it—a sunlit field nestled in a valley. Off to the right, in the distance, stood a wooden cottage with a churning waterwheel, and their mother waiting for them.

In the following loop, upon the boys’ arrival, she revealed herself as a sorceress when she’d moved from the cottage, and casually fought a monster with plant-based magic.

That would later become Chrysalis.

Two figures I’d imagined alongside her were an old woman in a wimple—Mary—and an older man with a hazy, indistinct presence. I knew only that he had windswept white hair and a white beard, and nothing more.

I knew the beginning of the story—the boys riding down a mountain—and I knew the end, which at one point had been the introduction of their villain.

From there, the official concept took shape: three boys—triplets—with titles reflecting the gifts bestowed upon them by their sorceress mother, destined to face a looming threat.

As for their father… Well, the boys were to serve as the weapon, the potion, and the animal companion to a “king.” In truth, they would be prophets to “The High King”—the equivalent of God in this world. Much like God and his prophet or messiah.

One complication was that I wasn’t particularly religious at the time. I’d grown up Catholic but had become somewhat agnostic. Many of the people I surrounded myself with were staunchly anti-religion, and I’d been made to believe that any association with it was inherently bad, homophobic, or otherwise harmful.

And yet, I’ve always loved the Nativity story. To me, it’s a wild, almost surreal concept—an angel descends from heaven to tell the Virgin Mary that she has been chosen by God to carry His Messiah, a child who would bring unity and peace, heal the world, and save God’s people. Some see it as a traumatic tale, a cruel burden placed on Mary—but that’s exactly why I admire it. Mary was the first truly badass woman. She’s a symbol of powerful femininity who took on a dangerous, strenuous task and saw it through to the end.

Unintentionally, my story became rich with biblical references, despite never planning it that way. Now, I couldn’t imagine it without them. But at the time, I had little more than a loose resemblance to the Nativity story—and that was all.

Since then, that idea and those characters lingered in the back of my mind, surfacing now and again, until COVID-19 began in 2020.

2020-2021

When the COVID pandemic hit, everything changed for me. I graduated university earlier than expected due to shutdowns and social distancing. The job I had at the time—an essential service—quickly became my permanent position. The graphic novel I had poured so much effort into, though it wasn’t my own story or vision, was placed on indefinite hiatus.

I was stuck in a difficult place. While I was grateful to have work, the job was miserable and exhausting, pushing me into what some might call “hermit mode.” My motivation faded, my passion for art waned, and no matter how hard I tried, I couldn’t reignite it. Even with small wins—like a successful Princess Tutu Kickstarter and a contracted internship—I began to lose hope of ever escaping the position I was in.

Looking back, many of those changes were blessings in disguise. I realized I wanted to create for myself—I had so many stories to tell. But as I still saw myself solely as a comic artist, it felt hopeless. Making a comic alone is grueling work, and my imagination was producing more stories than my art skills could keep up with.

2021 was a challenging year for me. While I accomplished things I was proud of, it was also a time of upheaval and deep self-reflection. I began questioning everything—myself, my purpose, and the direction of my life. Was I happy?

In the midst of this uncertainty, I turned to the one place that felt safe: my stories. I pulled Three Brothers Wise off the “brain shelf” and began fleshing it out again, letting it carry me away from the weight of reality. I wanted new beginnings, new connections, and a life that felt my own—and in my imagination, I could build that.

I planned the first five chapters, holding onto fragments of the original vision I’d once had for the beginning. Beyond that, the rest was open for discovery.

2022

Before this, I had dabbled in comics again—working on a fan-comic and the previous graphic novel. When that graphic novel fell through, it actually felt like a blessing, because it meant I could focus on my own stories once more.

Mostly, I was trying to reignite my motivation for art, so I rented my first official booth at Calgary Comic Expo. There, I met Cris Cameron, author of Cover of Darkness.

I asked her how she’d gotten started and stayed consistent—and how she found a team that truly worked with her. I shared my struggles with my previous team, how I’d poured in effort and saw the potential, but they hadn’t matched it. Worse, it hadn’t even been my story.

She told me she’d been lucky to find her tribe, a team in it for the long haul. Then, before I could finish explaining my lack of motivation and overwhelming ideas, she gave me advice that changed everything:

“Just write it. An idea can take you only so far, but writing it is what you can control. Whether as a screenplay, a novel, a script, or detailed bullet points—just write it. Figure out what to do with it once it’s written.”

That was all it took. I thanked her and stepped away, thinking, What? How was I—a comic artist who’d only ever imagined stories visually—supposed to put those stories into words?

I thought back to Three Brothers Wise, a story I’d always known was meant to be a novel—it was too complex to ever become a comic—but had never seriously considered writing it.

Taking Cris’s advice to heart, after the expo I settled down with my meager notes, my iPad, and a Google Doc, and began to write.

My writing was awful at first. But I fell in love.

Yet, in that moment, I discovered my purpose.

Inspirations

Stories are often inspired by one another. Even when they aren’t directly connected, concepts and ideas tend to overlap. Creators might not intend this or even be aware of other works influencing them, but every story contains pieces inspired by others—whether it’s a character, a concept, or an element of world-building.

While writing, I learned that how a story begins rarely matches how it ends. As I was mastering a new craft, I found myself listening to Terry Brooks’ Shannara Chronicles audiobooks, studying how Sarah J. Maas built the world of Prythian, and reflecting on my experiences in D&D campaigns during COVID. I also revisited J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, gaining new perspectives on storytelling and world-building.

Terry Brook’s The Origin and Genesis of Shannara

I found myself drawing the most inspiration from Terry Brooks, particularly Running with the Demon and Armageddon’s Children. I admired his skill at weaving complex characters and richly detailed worlds while exploring themes of good versus evil.

Both stories follow characters like Nest Freemark, John Ross, and Hawk. Brooks created “The Word” as his story’s equivalent to God—much like my version, “The High King”. The Void, opposing the Word, spawns demons by exploiting human doubts and desires. John Ross, a Knight of the Word, grapples with what it truly means to be a hero and the sacrifices it demands.

Brooks’ villain has a connection to Nest Freemark, which inspired the dynamic between my villain, Dyardaridge—also a demon—and my character Crow. Hawk, a child destined to fulfill a prophecy, also inspired Crow, Sage, and Lance.

More than anything, the questions Brooks raised about heroism and sacrifice helped shape the foundation of my story.

J.R.R Tolkien’s The Lord of The Rings and D&D

I wanted to include diverse races in my world, inspired by D&D and The Lord of the Rings. Amazon’s Rings of Power missed the mark by deliberately ignoring Tolkien’s rules surrounding Middle-earth. Tolkien designed elves in a very specific way for his story, and that should be respected. In contrast, D&D allows for more flexibility, letting creators play with the defining traits that establish a race.

Gary from Nerdrotic put it well: a fictional race is defined by its established features. Tolkien’s elves have pale skin, long slender bodies, pointed ears, and a heavenly grace that radiates from them. Netflix’s The Dragon Prince took this further by creating different types of elves, each with exclusive traits.

I asked myself: are races limited to humans and elves, or could anything be considered a race? What if sorcerers and sorceresses were their own race—the Sorceri? What if demons were also a distinct race?

In my world, races are defined by traits. My elves can have any skin tone but must have gold eyes, hair, freckles, and pointed ears. Humans vary based on their ethnic origins—The boys’ heritage reflects places in the real world: Crow’s heritage draws from Italian and Greek culture, Sage reflects Irish and Scottish roots, and Lance embodies Egyptian or Middle Eastern influences. Their designs reflect that in their final designs.

Sarah J. Maas’s A Court of Silver Flames and a conversation

When it comes to YA fantasy, I’ve still drawn inspiration from Sarah J. Maas—particularly one of my all-time favorite books, A Court of Silver Flames. I have a love-hate relationship with the series (which could be a whole separate post), but my main source of inspiration comes from her character work, world-building, and her use of the “mating bond” or soulmate concept.

That said, I’ve also found her world-building inconsistent, and my real spark of inspiration came from a conversation I had about how those bonds are used. The argument was that all the main characters seemed conveniently paired with their perfect match—making it predictable. For example, the next book in the series having Elaine end up with her mate Lucien would be expected, whereas a forbidden love between Azriel and Elaine would be more compelling. I disagreed, because there’s a deeper explanation for why they’d be incompatible—but the discussion highlighted something important: Maas often underutilized her own ideas.

In Wings and Ruin, Rhysand defines mating bonds as a connection between equals. He even notes that some bonds aren’t ideal—they could be beneficial, devastating, or entirely without love, as in the case of his parents. Equals could mean a match in experience, trauma, strength, power—it didn’t have to be romantic. Yet Maas never truly explored this complexity with her main characters.

That conversation also touched on how a 500-year-old being romantically involved with a 20-year-old is, frankly, unsettling—and I agreed. It revealed a missed opportunity: what if your “equal” was someone dangerous?

What if they were the villain—a truly evil villain?

I’ll leave it at that.

Biological Accuracy

Finally, my last source of inspiration came from my love of biology. As someone who dreams of starting a family, I wanted to highlight the power of femininity—to remind others that childbirth, pregnancy, and motherhood are not oppressive or belittling, but deeply powerful. Fertility and reproduction are extraordinary forces, and like the Virgin Mary, there’s awe in understanding what a woman’s body is naturally capable of.

Biological accuracy also reshaped the brothers in my story—from triplets to half-brothers. Yes, Chrysalis, the sorceress, could have simply been blessed by a messenger and magically conceived. But I couldn’t ignore the boys’ distinct appearances and the lack of resemblance to their mother. This led me to the concept of the Three Bloodline Kings—each with direct ancestry to The High King. For the sorceress to bear a child with unique abilities, she would need to conceive with each bloodline.

It was a bold and potentially controversial idea, but the more I shared it, the more intrigued people became.

So, I decided to run with it.

Writing Process

Every author has their own way of bringing stories to life. When people ask me how to stay consistent, I share the habit that’s worked best for me: start by writing it out by hand. That handwritten version is essentially your first draft—raw, unfiltered, and straight from your imagination.

Then, when you translate it into a digital document, it becomes your first edit. You naturally refine sentences, adjust pacing, and polish ideas, all while keeping the heart of the story intact. It’s like giving the story two births: one instinctive, the other intentional.

Outline and Ideation

I began writing by hand because my job at the time allowed me enough downtime to work on my story. I’d bring a clipboard and notepaper, jotting down chapters whenever inspiration struck. Later, I’d translate those handwritten pages into a digital document—turning my first draft into its first edit.

Inspiration comes in waves, and I’m a firm believer in writing down every idea immediately—whether it’s in your phone notes, on a scrap of paper, or scribbled in the margins of something else entirely. Even a single line of dialogue, a scene you might not use until much later, or maybe never—it’s worth capturing. Never trust yourself to remember it later, because you probably won’t. Yes, even at 3 a.m.—write it down.

For me, this is one of the clearest examples that writing is not a linear process. Inspiration can strike anywhere, and writing happens whenever you have the chance. When people ask about my process for The Eyes, The Sword, and The Remedy, my answer is always the same: it felt like the story wrote itself—I was just the one holding the pen.

Writing

When I first started writing in that Google document in 2022, I called my writing atrocious—and it was. No author should expect to know how to write perfectly from the start. The only chapter that remains almost exactly as it was is Sage’s perspective in Chapter Five.

The original beginning was slow, dull, and committed my biggest pet peeve: forcing characters to make stupid decisions just to move the plot forward. It opened exactly as my vision had begun—three brothers riding down a mountain into a valley to reunite with their mother. Crow, the eldest, experienced unsettling feelings and warned their mother about something strange he’d seen. Yet, instead of taking the warning seriously, she sent them into the forest for their next lesson: finding animal familiars.

From there, the plot unraveled with increasingly illogical choices. Crow, known for his cleverness and ability to learn anything, still allowed his brothers to wander off when strange events occurred—like a charred log suddenly collapsing into ash and he couldn’t explain why. Sage chased after the first rabbit he saw, conveniently leading them out of their mother’s protective veil. Over the span of five long chapters, very little happened before the actual inciting incident: they were ambushed, Crow was taken, Sage fell into a gorge, and Lance was left with the choice to pursue one brother or the other.

At the time, I knew little about what would follow Sage’s gorge chapter or about the huntsman, Cobb, who rescued him alongside their mother. Cobb was an enigma—originally imagined as an older man and a father figure to Chrysalis, not the boys—but beyond that, he was a blank slate.

Because I was stuck, I jumped ahead to the end. Even without knowing my villain in detail, I knew he wanted Crow, and that’s when he would capture him—revealing the truth about his mother’s mysterious past. This led me to write Chrysalis’s chapters, culminating in her encounter with a soldier who served under a Bloodline King—the former general Cobalt—who looked younger than his years and made a promise to her.

That’s when Cobb’s character finally came into focus, inspiring an entire backstory that let me return to Chapter Six and move forward with the story. My influences—pieces from Terry Brooks, Sarah J. Maas, and my own developing ideas—shaped my villain Dyardaridge, his connection to The Bloodline Kings, and his tie to Chrysalis.

Because my early draft was barely legible, I decided to rewrite everything with my growing worldbuilding in mind. Chapters formed in fragments, written in the order inspiration struck.

I often say my story wrote itself, because for much of it, I had little idea where it was going. My “outline” was nothing more than a long strip of glued-together paper scraps, each bearing the next idea. The next chapter would appear to me in fragments—one idea leading to another, which might inspire something for later, or something to weave in throughout the story. At some point, I had more planned for the books later in the series, with ideas and plot threads I needed to foreshadow or allude to early on.

An idea that didn’t work in one place often found its perfect home somewhere else. With each chapter, I filled a folder to bursting—paperclipping smaller ideas to the main draft like puzzle pieces waiting to lock into place. However, I wouldn’t edit anything until the first draft was complete. I’d make note of what to fix later.

Those ideas revealed to me that I’d need to go back and rewrite earlier sections, because the characters began to tell their own stories. They revealed themselves—their needs, wants, desires, fears—everything. Character qualities shifted. Cobb developed unexpected depth, driven by secrets he’d been hiding for Chrysalis. Chrysalis’s demeanor evolved as did her psyche. Dyardaridge became fully realized, no longer just a shadow of a villain, but a living, breathing force in the story.

First Draft

By the end of 2023, I had nearly finished the first draft. But that time also marked the beginning of a new wave of mental turmoil. A longtime friendship fell apart, and I was breaking away from relationships that were no longer healthy. I began truly recognizing my traumas, struggles, and pain. It was a year of grueling, painful healing.

I became reclusive, overwhelmed by being around others—especially those I couldn’t open up to. I grew cautious about who I spoke to and who I trusted, and those I could rely on were revealed to me. Writing the novel became my only safe haven, my escape from a stressful reality. My goal was simple: finish the damn story.

“Just write it. Figure out what to do with it once it’s written.”

Those last ten chapters were the most painful—not because they were hard to write, but because the words poured out with ease, raw and unfiltered.

Those chapters were brutal healing. I realized that each character held a piece of me—a wound or trauma I’d carried my entire life—and I was finally confronting each and every one of them. Many of my characters cried because I was crying.

Finishing the story was surreal. It was a process of allowing—not just the story, but myself as the author—to experience growth and healing. You can’t force what doesn’t work; you must embrace what comes naturally. Characters decide who they are for a reason.

For me, this story showed me everything about myself I wasn’t aware of.

Physical Creation

My original expectation for The Sons of Prophecy series was a duology. Two books quickly became four, and four became five with two novellas. Stories evolve during the writing process, and mine was no exception. The fourth book wasn’t even intended until a one-off character—created for a single chapter—sparked a flood of inspiration. I began asking myself questions about them, and the answers unraveled into an entirely new story.

I don’t like loose ends. If a question can be asked, I want it answered. This single character, who took shape as I wrote them, ultimately created a fourth book that slotted perfectly between the third and what was meant to be the final installment.

Being aware of what my series consisted of, I could flesh out the design of it. Because of my background in art and design, I was able to fully bring my vision for the series to life. I designed the characters, dust jackets, cover art, and even the series logo myself—every detail crafted to match the world in my head.

Even the fifth book already has its title and a work-in-progress cover design… but it’s a major spoiler for my readers, so it won’t be released until much later.

Thanks to my experience with Kickstarter, I successfully launched a campaign that funded the book. The decision to self-publish opened unexpected opportunities—leading me to supportive communities, connecting me with people who believed in the project, and ultimately bringing my first editor into my life. She was a friend introduced to me by my boyfriend, and she proofread the final draft.

I later invested in a second editor to help condense and refine the story—because, somehow, someone who once struggled to reach the minimum word count on school essays had managed to overwrite a novel.

Self-publishing taught me just how invaluable editors and proofreaders are, and that cleaning up a manuscript is far from easy. Word of advice: never hand your editor a stew of mixed tenses. Clean it up first, because editing is hard enough without the chaos. My editors not only improved the manuscript, they gave me incredible feedback that taught me more than I could have imagined.

Despite the mental hoops I had to jump through, 2024 was a productive year. The novel became the centerpiece of a new chapter in my life, funneling me toward my purpose. Over obstacles and through challenges, I manifested it into reality. I had my vision for the hardcover—and I made it real.

Conclusion

Like J.K. Rowling, every author’s journey is long and winding. She’d sold millions of copies of Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone fifteen years after first imagining Harry, Ron, and Hermione when her train stalled for four hours. She’d endured divorce, moved countries, trained as a teacher, and became one before she was ever published.

What began as a bedtime story for his children, J.R.R. Tolkien spent two years writing The Hobbit and another three revising it before it was ready for print. One spark became the start of one of the greatest literary journeys in history.

Terry Brooks, like Rowling, wrote while working full-time and studying law, maintaining his discipline until a literary agent connected him with the right person.

Writing isn’t linear—it’s a string of lucky breaks, chance meetings, relentless consistency, and often years of struggle. Stories have a way of writing themselves. You might begin with one character and end with ten, each with their own lineage, history, and connections you never planned for. Even side characters with a hinted past can spark entire subplots and timelines. As the author, you’re simply the one documenting the lives and the world they reveal to you.

When I started, I thought I needed 8–11 pages for a chapter, without realizing I was writing on 8"x11" paper instead of the smaller print size. I switched from third person to first, and from present tense to past, halfway through. Editing was a battle, and trusting someone else with my story was hard—but necessary. The final draft proved it was worth it.

A project like this reveals a lot—who truly supports you, who only claims to, who cares for you, and who doesn’t. Now, as I dive into the first draft of the sequel, Twisted Loyalty, I can already tell it’s messier than the last.

Writing is not a simple activity. An author is not someone sitting serenely at a desk with tea and a smile, typing a flawless story from beginning to end. It’s obstacles, messy ideas, and constant rewrites. It’s jotting dialogue on the back of receipts, on your hand, or—yes—even a scrap of toilet paper. It’s broken relationships giving way to real, stronger ones. It’s mental breakdowns and shattered self-identity, only to find yourself again through the ashes.

It’s waking at 3 a.m. because the next chapter refuses to let you sleep.

Writing is the author, and the author is a mess.

Writing is not simple.

Writing is not linear.